The Eastern Orthodox say the Filioque is not merely unauthorized modification of the Creed, but even that the Filioque is actually heresy because the EO claim that "proceeding" is a technical theological term that is reserved exclusively for the relation between the Father and the Holy Spirit. So in their mind, "proceeds" is used as the 'unique identifier' for the Third Person of the Holy Trinity. Similarly, the EO hold that "begotten" is reserved exclusively for the relation between the Father and the Son, so "begotten" is the 'unique identifier' for the Second Person of the Holy Trinity. The terms "begotten" and "proceeds" are 'actions' performed by the Father alone, and these two unique actions are the only 'thing' that distinguish the Three Persons in the Trinity. For example if there are two persons being "begotten" by the Father, then this would mean there are two sons in the Trinity, which is heresy. So the Holy Spirit must be something different than "begotten" by the Father. Similarly, it is said if the Son can produce a Person, then the Son would become another Father, which is also heresy. So the EO hold that the only way to prevent duplicate persons is the "Unbegotten Father; Begotten Son; Proceeding Spirit" understanding of the Trinity. This argument is fair and relatively straightforward. The main problem is that there is no official definition for what "proceeding" is, so it is actually impossible to formally say the Son cannot also be involved in some way with "proceeding," and some Catholics have argued that without the Son's involvement, then "proceeding" would be indistinguishable from "begetting". Historically, the bulk of the Filioque dispute with the EO has been over what "proceeds" actually means, since without having agreement on that term, it is extremely difficult to come to doctrinal agreement.

What is amazing about the argument made by Nathaniel in the YouTube discussion was that he explained that the Nicene Creed was never meant to dogmatize terms like "proceeding," but rather was focused more narrowly on affirming the Divinity of the Son and Holy Spirit. As long as a Christian affirmed the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit was Divine, then that Christian was orthodox. If Nathaniel's claim is indeed the case, then terms like "proceeds" cannot be turned into church-dividing issues, because such detail is outside the goal of the Creed. If you talk to the average practicing Christian who knows the Creed, they aren't even aware of such sophisticated details. Let's consider some reasons why the Creed never intended to turn "proceeds" into a crucial sophisticated theological term:

- There were multiple orthodox Creeds that came about in the Early Church prior to the Nicene Creed in AD325. Philip Schaff documents [here] around ten different orthodox creeds going around prior to Nicaea. These Creeds all agree in essence with each other, but they use different language at times. Yet this different language did not automatically entail controversy or cause divisions in the early Church. This different language was typically to make it easy for the average person to affirm orthodoxy, or to address unique problems within that region. You will notice that language of "begotten" is not really used until closer to Nicaea, and that "proceeds" is even less used. So it is safe to say these terms were not originally seen as crucial key terms for orthodoxy. What these Creeds do show is that the goal was to teach the Three Persons of the Trinity, and that they were of the same nature, divinity, God(head).

- The Council of Nicaea in AD 325 gave us only the first 'half' of the Nicene Creed we use today. The other 'half' of the Nicene Creed came at the Council of Constantinople in AD 381. This chart (here) compares the wording of the original 325 and expanded 381 versions of the Nicene Creed. When you look at the original Nicene Creed of 325, you will see that it abruptly ends with "And I believe in the Holy Spirit." Notice that there is no mention of "proceeds from the Father". This lack of "proceeds" is strange if the Creed was composed in order to intricately distinguish Persons in the Trinity. But the lack of "proceeds" is not strange if Nicaea was never really about intricately distinguishing persons, but rather about affirming the "consubstantial" status of the Son as having same Divine Nature as the Father. The principal thing "begotten" is said to do here is differentiate from

the Son being "not made" (i.e. not a creature).

- Looking into this more, I found a blog post [here] that discusses how only anathema at 325 Nicaea was "For those who say 'There was a time when he was not;' and 'He was made out of nothing,' or 'He is of

another substance [Gk hypostasis] or essence [Gk ousias]' they are condemned by the holy catholic Church." [Green & English text here]. In other words, condemned are those saying the Son was not eternal or those saying the Son was of a different substance/essence from the Father. This anathema is focused strictly on the eternality and the nature of the Son. This was probably on purpose, because notice that the 325 Nicaea anathema equates hypostasis with ousias, both meaning substance/essence. This is fascinating because the term hypostasis later came to mean the opposite of substance/essence, that is hypostasis later came to mean person. Clearly, when Nicaea condemned those who say "the Son is a different hypostasis" from the Father, that cannot mean "person" at that time. This is significant because it shows that even key theological terms can and have developed, even significantly, which again would mean we must be careful not to condemn or put too much emphasis on a term like proceeds which could be subject to similar different understanding. Note that the original 325 Nicaea anathema was dropped at the 381 Creed, along with the original 325 Nicene Creed sentence "And in one Lord Jesus Christ,

the Son of God, begotten of the Father the only-begotten; that is, of

the essence [ousias] of the Father, God of God, Light of Light, very God of very

God, begotten, not made, being of one substance (homo-ousias) with the Father." By dropping the Nicene anathema and the line "the only-begotten; that is, of

the essence [ousias] of the Father," this signifies to me a shift/development in thinking about how we are to understand key terms and concepts. The claim "only begotten" here seems to be defined as the Son is born from the Father's essence, which later Trinitarian theology would say isn't accurate.

- St Jerome in his Letter 15 to Pope Damsus in 377 expressed deep concern about the use of hypostasis suddenly taking a different meaning. St Jerome writes: "Order a new creed to supersede the Nicene; and then, whether we are Arians or orthodox, one confession will do for us all. In the whole range of secular learning hypostasis never means anything but essence. And can any one, I ask, be so profane as to speak of three essences or substances in the Godhead? There is one nature of God and one only; and this, and this alone, truly is." This was written just a few years before the Council of Constantinople in 381, and per this letter, people were accusing Jerome of being a heretic for him opposing the use of the Greek term hypostasis being used to refer to persons, as we saw above it later came to be (e.g. "hypostatic union"). A Greek scholar like Jerome was aware the term hypostasis had always simply meant essence, so on what basis was such a set term suddenly re-defined? It seems to me that if we are going to be fair to the West, that we admit Greek words were significantly altered by Church Fathers in the East.

- The Armenian Orthodox (not EO) have their own modified version of the 381 Creed, but it was not accused of heresy. Yet when you look at the wording (here) you will see that it adds quite a bit of its own commentary, and it does not use the term "proceeds" at all. It says: "We believe also in the Holy Spirit, the uncreated and the perfect; who spoke through the Law and through the Prophets and through the Gospels; Who came down upon the Jordan, preached through the apostles and dwelled in the saints." Notice instead it refers to the Holy Spirit as "uncreated and perfect," which pertains to having the Divine Nature. So as with the 325 Creed, it most likely means the original understanding of the Nicene Creed was to teach the divinity of the Son and Holy Spirit, and not concerned about details of distinguishing Persons.

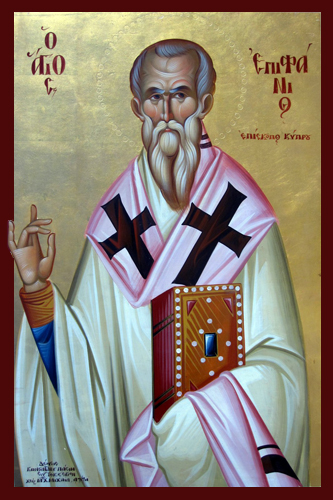

- The Baptismal Creed of Jerusalem written by St Epiphanius around the year 374, i.e. right between 325 Nicaea and 381 Constantinople, uses nearly identical language that the 381 Creed uses (though maintains Nicaea's "of the substance of the Father"), meaning the 381 Creed was largely a copy of existing Baptismal Professions. But when you look at the Epiphanius Creed (here), it is considerably longer than the 381 Creed, indicating that Creeds were often modified to address heresies at that time, so long as they maintained the essential Nicene character of affirming the consubstantial nature of the Son and Father. While the Epiphanius Creed does mention "proceeds from the Father, received of the Son," a sort of semi-filioque statement, the really interesting point is how it only mentions "proceeds" once in passing, while spending several sentences emphasizing divinity of the Son and Holy Spirit. Even the anathema attached is the same as 325 but now includes "and the Holy Spirit" after every affirmation of the Son, including using both hypostasis and ousias in the same synonymous sense as Nicaea. In other words, it seems clear the Epiphanius Creed was more interested in emphasizing the Son and Spirit were Divine just as much as the Father is, and not so much interested in teaching key terms for differentiating Persons.

- Canon 5 (sometimes labeled Canon 4) of the 381 Council of Constantinople says (here): "In regard to the tome [creed] of the Western Bishops, we receive those in Antioch also who confess the unity of the Godhead of the Father, and of the Son, and of the Holy Ghost." This canon suggests that Constantinople recognized other Creeds as long as divine consubstantiality was being affirmed, and thus not so much focused on "proceeds" as a key term to differentiate the Persons.

- The last but not least of the points that Nathaniel made was that the 381 Creed (and others) most certainly have Revelation ch22 in mind when speaking on the Holy Spirit, but the statements are more to emphasize divinity rather than differentiate Persons. Consider that we see the 381 saying we believe in the Holy Spirit, Who is (a) Lord, and (b) Giver of Life, and (c) Who proceeds from the Father [and Son], and (d) with Father and Son is adored. Each of these statements emphasize that the Holy Spirit is "Lord," and not so much concerned about distinguishing the Persons. The language of "giver of life" in Greek is only found in Rev 22. The Greek term "proceeding" from Father (and Son) is found exactly in Rev 22:1 (and in a different form in John 15:26). The adoring alongside the Father and Son comes from Rev 22, where John bows to the angel and is told by the angel "do not worship me, instead worship God". Revelation 22 is about highlighting the divinity of the Holy Spirit. I've written about the Revelation 22:1 usage of the term "proceeds" for both the Father and Son, but Nathaniel is simply arguing that we don't even need to emphasize this, since the main point John is making in Rev 22:1 is that the Holy Spirit is divine, not that we need to somehow distinguish the Holy Spirit, especially if nobody was even confusing the Holy Spirit with the Father or Son.

- Schaff notes, and is known by many others, that the original Nicene Creed of 325 was seen as the authorized Creed up until the 381 Creed was admitted at Chalcedon in 451. This means that, technically, the 325 Creed still reigned for seventy years after 381 Constantinople, and even through the AD431 Council of Ephesus. This means that terminology up until at least 451 was still not fully settled upon, and so we cannot terribly fault those Latins in the far western half of Europe who might not fully understood that proceeds had begun to take on a intricate key meaning in the East.

|

| St Epiphanius |

8 comments:

The link on the Armenian Church point is not working to me.

Not meaning to add anything to the discussio, i can't, but it is interesting how something that at least looks so trivial to the ancients can be dividing later.

Thanks for that, I corrected the link.

Thanks as well! It is a interesting finding.

@Talmid it's all starded with very prideful, arognat, and greek chuvanist (not his personal problem tho, Byzantine civilisation does not belive in aristotelian "unity in diversity" but in uniformism) clergyman called Photius that was the cuase of Eight ecumenical council. He wanted to elevate Constantinople at the cost of Rome so he attacked all western practices, Filioque compared to rest of his attacks at least have semisemblance of theology behind it.

Thanks for the tip, Reksio! Will check the guy out.

I thought the stuff about Jerome to be especially interesting.

In addition to point #3 above, the original 325 Nicene Creed, it turns out that the Greek word Hypostasis appears in the Bible a few times, mostly meaning "confidence". The term means generically "sub-stance", that is a foundation, or essence of something. It is used by Paul to mean "confidence" in 2 Cor 9:4; 11:17; and Heb 3:14. In Hebrews 11:1, it is used for "faith is the substance of things hoped for..."

But the remaining instance in Hebrews 1:3 is the most fascinating:

"3 He [the Son] is the radiance of the glory of God and the exact imprint of his nature [hypostasis], and he upholds the universe by the word of his power."

This is the one time hypostasis is used of God in the New Testament that I'm aware of. It refers to the 'nature' of God and not to "personhood" (as it later came to mean in post-Nicene theology and common usage). Here it says the Son has/is the same hypostasis as the Father, which obviously cannot mean the same person as the Father, but instead must mean "essence/nature". This is an interesting point because it further solidifies the overall point of this post, which is that the Creeds have their limitations in how/what they were intending to convey, and that even terms like Hypostasis must be used more flexibly that what some have done such as to cause unnecessary division in the Church.

https://www.blueletterbible.org/lexicon/g5287/kjv/mgnt/0-1/#lexResults

On top of that, I'm looking into where the Greek term "Ousia" (what we call "essence/nature") appears in the Bible, and it looks like in the New Testament it only appears twice, in the parable of the Prodigal Son (Lk 15:12-13), referring to "allotment of goods" that the prodigal son said was his share of the estate. So this really isn't even a common term for "nature/essence" in the Bible. The Lexicon says it refers to "what one has, property, possessions," so I can see how God gives what He has to the Son in the Trinitarian sense of giving God's Divine Nature to the Son.

This Biblical analysis is important in that it looks like Hypostasis is a generic term used a few times and only once for God (Heb 1:3), while Ousia is a similar generic term, used rarely and never for God. From this we can see why the Council of Nicaea would be so controversial, especially to Bishops who spoke Greek, because such terms were not really used Biblically and thus had a sort of new terminology being introduced. This isn't in itself a problem, but it is basis for some hesitation and objection, especially when these terms took on different meanings not only at Nicaea 1, but then 50 years later at Constantinople 1.

https://www.blueletterbible.org/lexicon/g3776/kjv/tr/0-1/

Post a Comment